- Introduction to Subjective Methods

- Birth weight

- Body shape

- Weight and height

- Waist and hip circumference

- Introduction to Objective Methods

- Simple measures - stature

- Simple measures - weight

- Simple measures - circumference

- Simple measures - arm anthropometry

- Simple measures - skinfolds

- Simple measures - abdominal sagittal diameter

- Simple measures - head circumference

- Bioelectric impedance analysis

- Multi-component models

- Hydrostatic underwater weighing

- Air displacement plethysmography

- Hydrometry

- Whole body DEXA scan

- Near infrared interactance

- Whole body counting of total body potassium

- 3d photonic scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) / Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)

- Total body electrical conductivity (TOBEC)

- Computed tomography (CT)

- Ultrasonography

- Introduction anthropometric indices

- Body mass index

- Fat and fat free mass indices

- Ponderal index

- Percentiles and Z-scores

- Anthropometry Video Resources

- Height procedure

- Protocol for measuring waist circumference

- Measuring hip circumference

- Weight and body composition procedure

Body shape

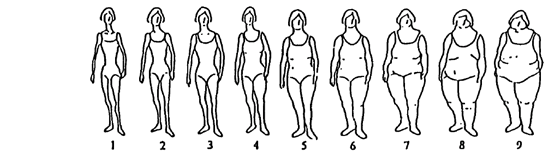

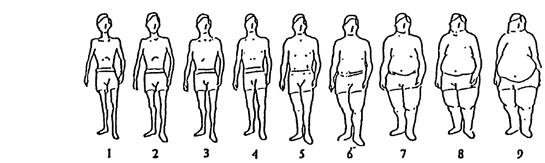

The body silhouette images tool is a psychometric test, originally developed by Stunkard and colleagues in the 80’s for Caucasian body builds, although culturally relevant body image tools are also available. It illustrates a series of line drawings of men and women of distinct body sizes (from extreme thinness to extreme obesity). The scale has been successfully implemented to recall current and past body shape, including parental body shapes.

Although individuals have a tendency to perceive themselves as slimmer than they actually are and underestimate their weight status, there are strong correlations between measured BMI and figure ratings assigned by respondents and by unrelated observers, suggesting that this method can provide valid information about body shape and weight.

From a series of images (see Figure A.2.2 for example), individuals choose the body shape which best depicts either:

- Their current body shape

- Their body shape at a given earlier age or ages

- The body shape of their parents at a given age (e.g. middle age)

Figure A.2.2 Example of body silhouette rating scales used for females (top) and males (bottom) as used in the Fenland Study General Questionnaire. Participants choose the image which best depicts their body shape. This can be repeated for current and for previous body shape (e.g. at ages 10, 20, 30, 40). Participants can also choose the body image which most accurately reflects their parents’ body shape during middle age. Source: [13].

Selection of data source

The data can be collected by interview, can be self-administered, or be collected by an independent observer (e.g. friend or family member). They can be administered using pen and paper or an electronic device such as a mobile phone, tablet or computer, either face-to-face or remotely (e.g. by post or internet). Use of photographic or 3D images rather than illustrations is a recent option that may better represent different body types (e.g. individuals with wider hips or broader shoulders).

Obtaining cost-effective yet reliable measures of shape and weight is often difficult in large-scale surveys and epidemiological studies, especially in resource constrained settings (e.g. low income countries). The body shape tool can be used as an alternative in these scenarios. It is also an option for individuals who are reluctant or are too self-conscious to be measured objectively.

It is also used to study self-perceived body image and to rate attitudes regarding ideal body shape. The discordance with objective body weight and BMI may be informative.

An overview of subjective body shape methods is outlined in Table A.2.4.

Strengths

- Low cost

- Low survey time

- Easy to administer via study questionnaires, via mail, face-to-face interviews or the Internet

- Can be self-administered

- Applicable outside laboratory settings

- May be applicable and acceptable in different cultures/ethnicities as culturally relevant body image tools are available

- Can be collected retrospectively

- Low respondent burden

- Large number of individuals can be approached

- Non-intrusive

- It could increase recruitment rates and participation retention, especially by individuals who are reluctant or are too self-conscious and embarrassed to be measured

- No fieldwork required if self-administered or collected online

- Requires no equipment and no specially trained staff

- Feasible in settings with low levels of literacy or in studies including older individuals, where recall bias might be high where the use of self-reported weight is limited

Limitations

- Prone to differential systematic errors in reporting by body size and socio-demographic characteristics

- Prone to response bias e.g. social desirability

- May not be feasible in populations where recall bias is high (e.g. misidentification is more frequent in older individuals compared to younger groups)

- Images/illustrations may not capture all the different body types (e.g. individuals with wider hips or broader shoulders)

- Body image tools may not be always available for a specific population

- Limited number and range of figures are presented on the scale

- As the scale data are ordinal, parametric statistics may not be applicable

Table A.2.4 Characteristics of subjective body shape methods.

| Characteristic | Comment |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | High |

| Relative cost | Low |

| Participant burden | Low |

| Researcher burden of data collection | Low |

| Researcher burden of coding and data analysis | Low |

| Risk of reactivity bias | No |

| Risk of recall bias | Yes |

| Risk of social desirability bias | Yes |

| Risk of observer bias | Yes |

| Space required | Low |

| Availability | High |

| Suitability for field use | High |

| Participant literacy required | Yes, if self-administered |

| Cognitively demanding | Yes |

Considerations relating to the use of subjective body shape methods in specific populations are described in Table A.2.5.

Table A.2.5 Use of subjective body shape methods in different populations.

| Population | Comment |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy | |

| Infancy and lactation | |

| Toddlers and young children | |

| Adolescents | |

| Adults | In general, men tend to misperceive their overweight status as normal more frequently than women. |

| Older Adults | Older individuals mis-identify overweight status as normal more frequently than younger groups. |

| Ethnic groups | Validity may vary by ethnic group. |

| Other | Individuals with lower socio-economic status are more likely to underestimate their weight status. |

- Trained interviewers for interviewer-administered tools

- Instructions for completion and return

- For mailed questionnaires a pre-paid stamped address envelope

- Standard operating procedures for interviewers and coding

- Data entry cleaning code

A method specific instrument library is being developed for this section. In the meantime, please refer to the overall instrument library page by clicking here to open in a new page.

- Acevedo P, Lopez-Ejeda N, Alferez-Garcia I, Martinez-Alvarez JR, Villarino A, Cabanas MD, et al. Body mass index through self-reported data and body image perception in Spanish adults attending dietary consultation. Nutrition. 2014;30(6):679-84.

- Adami F, Schlickmann Frainer DE, de Souza Almeida F, de Abreu LC, Valenti VE, Piva Demarzo MM, et al. Construct validity of a figure rating scale for Brazilian adolescents. Nutr J. 2012;11:24.

- Bulik CM, Wade TD, Heath AC, Martin NG, Stunkard AJ, Eaves LJ. Relating body mass index to figural stimuli: population-based normative data for Caucasians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(10):1517-24.

- Cardinal TM, Kaciroti N, Lumeng JC. The figure rating scale as an index of weight status of women on videotape. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(12):2132-5.

- Collins ME. Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children Int J Eat Disord 2006;10(2):199-208.

- Conti MA, Ferreira ME, de Carvalho PH, Kotait MS, Paulino ES, Costa LS, et al. Stunkard Figure Rating Scale for Brazilian men. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(3):317-22.

- Harris CV, Bradlyn AS, Coffman J, Gunel E, Cottrell L. BMI-based body size guides for women and men: development and validation of a novel pictorial method to assess weight-related concepts. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(2):336-42.

- Mak KK, McManus AM, Lai CM. Validity of self-estimated adiposity assessment against general and central adiposity in Hong Kong adolescents. Ann Hum Biol. 2013;40(3):276-9.

- Nagasaka K, Tamakoshi K, Matsushita K, Toyoshima H, Yatsuya H. Development and validity of the Japanese version of body shape silhouette: relationship between self-rating silhouette and measured body mass index. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2008;70(3-4):89-96.

- Pulvers KM, Lee RE, Kaur H, Mayo MS, Fitzgibbon ML, Jeffries SK, et al. Development of a culturally relevant body image instrument among urban African Americans. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1641-51.

- Scagliusi FB, Alvarenga M, Polacow VO, Cordas TA, de Oliveira Queiroz GK, Coelho D, et al. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Stunkard's figure rating scale adapted into Portuguese. Appetite. 2006;47(1):77-82.

- Sherman DK, Iacono WG, Donnelly JM. Development and validation of body rating scales for adolescent females. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18(4):327-33.

- Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;60:115-20.

- Swami V, Salem N, Furnham A, Tovee MJ. Initial examination of the validity and reliability of the female photographic figure rating scale for body image assessment. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44(8):1752-61.

- Yepes M, Viswanathan B, Bovet P, Maurer J. Validity of silhouette showcards as a measure of body size and obesity in a population in the African region: A practical research tool for general-purpose surveys. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13:35.